Interest Rate Arbitrage

I have always been curious of the way Interest Rates work. Something really fascinating about how different countries are able to borrow at different rates with multitude of future predictions baked in. Also, I have always wondered whether it is efficient for a developing country like India to borrow from International markets like United States at a cheaper rate.

In the 2019 budget speech, the government of India proposed a plan to issue 10-year bonds denominated in foreign currency. The proposal was met with intense ire from renowned economists. To quote former RBI governor, Raghuram Rajan,

Foreign bankers often meet finance ministry officials, trying to persuade India to issue a foreign bond. In my experience, they usually started by saying that such borrowing would be cheaper because dollar or yen interest rates are lower than rupee interest rates. This argument is bogus—usually the lower dollar interest rate is offset in the longer run by higher principal repayments as the rupee depreciates against the dollar.

Let’s try to explain the above with an example:

Year 2012, India 10 Year Bond yield (INR): 8.12% and US 10 year bond yield (USD): 1.64%

Spread = 8.12-1.64 = 6.48%

Now, if the yield on a US 10 year bond is 1.64%, we will have to factor in Emerging market risk to get the approximate yield for India 10 year bond (denominated in USD).

Based on datapoints from Indonesia, another developing country, with a similar risk profile as compared to India, (Slightly riskier as their debt denominated in FCY as a percentage of GDP in much higher) we will consider the yield for 10 year GoI bonds (USD) to be 3.14%. 1.5% higher than the US 10 year bond yield.

Difference between India 10 year bond yield denominated in INR vs USD = 8.12% - 3.14% = 4.98%

If we compound 4.98% over 10 years, this bond reduces GoI’s borrowing cost by 62%.

Well, let’s not hurry to our conclusion. Why does Raghuram Rajan think that this pitch of lower borrowing cost is bogus. To understand that, let’s look at USD-INR rate for the last 10 years.

The USR-INR conversion in July, 2012 was Rs 55, the current price is Rs 80.

Cumulative Depreciation over 10 years = 45% (80−5555)

Average Annual Depreciation = Solveforx:(1+x)10=1.45

x = 3.8%

Wait what? The depreciation cost associated with this USD denominated bond is 3.8%, however, the savings as we calculated above is 4.98%, giving us a healthy buffer of 1.18%. This means that even if cost of borrowing in USD increased by 50 bps (0.5%), Government of India would have made a profit of 10% by issuing this bond in USD compared to INR.

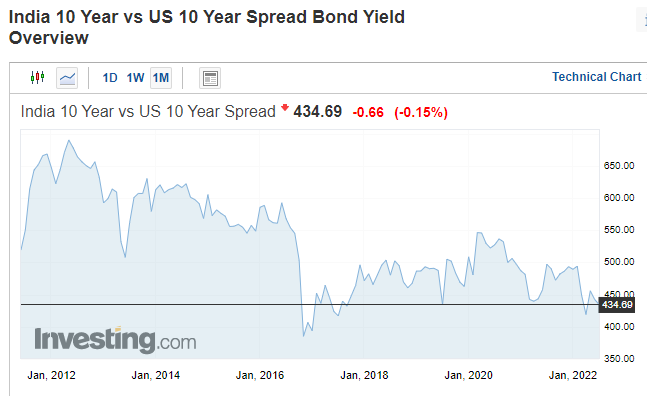

Before I call it a day, let’s look at one more chart.

From 2012 till 2016, the spread between Indian 10 year bond (INR) and US 10 year bond was quite high, and by pure coincidence, the spread was at its peak around Jun-Jul 2012. (Exactly 10 years earlier) and therefore, the above calculations showed a profit of 17% for GoI if they issued the same bond in USD. However, the spread has come down over the last few years, implying that such a trade might not be profitable. It depends on timing and the long term depreciation of INR wrt USD. Also, for the sake of this essay, we assumed emerging market risk to be 1.5%, however, if we look at recent borrowing data, this number is around 1%, and should be even lower for India given our low debt in FCYs to GDP ratio and healthy foreign reserves.